New research selected by Health Affairs’ Editor in Chief as work that moves the field forward and needs more attention

Personal care aides (PCAs) play a vital role in ensuring that people with disabilities and older adults remain in their homes and communities, but according to recent research by Healthforce Center’s Susan A. Chapman, Laura Wagner, and Timothy Bates, in partnership with Rayna Sage and colleagues at the University of Montana, there is a shortage of these workers throughout the United States, particularly in rural areas.

This means that many people who wish to remain in their homes end up in nursing homes or face the consequences of going without the care they need and may ultimately face excess morbidity and mortality. As the baby boomer population continues to age, the demand for in-home services and long-term care will only increase.

“This issue is not going away, and we must do everything possible to attract and retain workers as personal care aides in these high-need areas,” Chapman said.

The team’s research — which was published in the journal Health Affairs in October and selected as a Health Affairs Editor’s Pick for 2022 to highlight this important issue — is the first of its kind to identify potential shortages by linking the availability of workers to the potential demand for services across different geographies.

Who Are PCAs and What Do They Do?

Personal care aides provide in-home services to people with disabilities and older adults and make it possible for clients to live in their homes instead of care facilities. The services provided include assistance with eating, bathing, and dressing; transfers into or out of a bed or chair; household activities like light housework, laundry, meal preparation, or grocery shopping; and transportation to health care appointments.

The research data reflects that in both rural and urban areas, the vast majority of personal care aides are female. PCAs in rural areas are predominantly white (74.9%) and in urban areas they are predominantly nonwhite. In urban areas, PCAs are more likely to be foreign born or speak a language other than English at home. These differences in race, place of birth, and language for PCAs reflect the broader populations in rural and urban areas. These factors may be important considerations for recruiting, training, and retaining PCAs.

“We should do everything we can to keep people with disabilities where they want to live,” said Rayna Sage, PhD, Chapman’s research partner and the project director for the Research and Training Center on Disability in Rural Communities at the University of Montana.

“We should stop relying on PCAs’ willingness to go above and beyond,” Sage said. “For some people PCAs are the most important people in their lives and are the only people they see.”

“A Poverty Wage Job”

The estimated 1.3 million PCAs in the United States make an average of $13 per hour (Weller et al., 2020). This results in nearly 19% of PCAs living below the federal poverty threshold, whereas the average across all other occupations in the US civilian workforce is 6.8%. In addition, the percentage of personal care aides with health insurance coverage is lower (80.2%) than the average across all other occupations (87.8%).

“This is a poverty wage job,” Chapman said. And many workers providing health related services are not able to afford health insurance for themselves.

A Geographic Mismatch

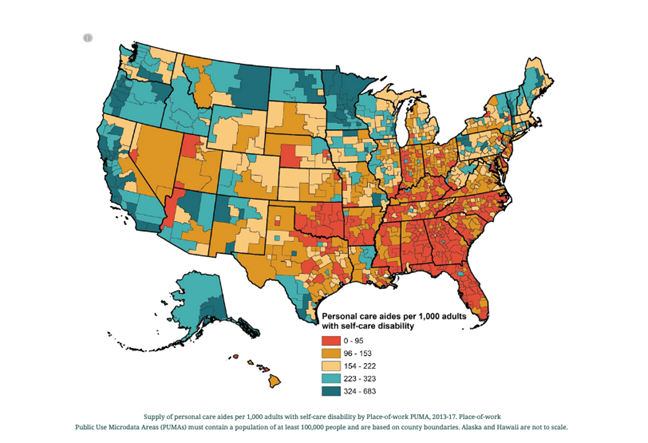

A disproportionate percentage of people living in rural communities report self-care disabilities and yet those regions have fewer PCAs to meet peoples’ needs. Scarcities are also exacerbated in the South and pockets of the Midwest and West.

Number of Personal Care Aides per 1,000 Adults with Self-care Disability

Source: Personal Care Assistance in Rural America, University of California San Francisco and University of Montana, Dec. 14, 2022.

While Medicaid pays for some long-term services and supports (LTSS), the program benefits, especially for home and community-based services, are inconsistent across states. States, mainly in the South, many of which have opted out of Medicaid expansion following the Affordable Care Act, are also some of the same areas facing the worst potential shortages of PCAs including Texas, Mississippi, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, and Kansas.

Another source of information on LTSS services by states is the The Long-Term Services & Supports Scorecard from AARP that provides rankings of long-term services and supports for older adults, people with physical disabilities and family caregivers, demonstrating the wide range of performance across states and geographies. While states are required to cover benefits for nursing facilities, coverage of home and community-based services is optional, and spending varies by state. In some areas community-based organizations have stepped up to fill the void, but this remains inconsistent across the country.

Photo Mapping the Caregiver Experience: “It’s a Human Connection”

In addition to the quantitative analysis, Sage and her team asked PCAs to document their work environments with photos. “We were so grateful that these incredibly hardworking and compassionate women were willing to share their stories and photos with us — they are doing really important work,” Sage said.

Barbara, a PCA in Alaska who has provided care for most of her adult life, says she takes pleasure in knowing that she is making a difference in the lives of people who might not otherwise be able to participate in important life moments like weddings. “That I could enjoy watching her participate in the wedding and just be there and be herself.”

Another PCA featured in the photo map, Jennifer, is 34 years old and lives in a rural community in eastern Arkansas. She has been providing paid home care for her grandmother for more than two years. She formerly provided care in a long-term living facility, in addition to providing home care for other friends and family members. Jennifer is enthusiastic about caring for friends and family members and ensuring they are able to remain in their homes and active in the community.

"Before I lived here, she was only getting to go to the grocery store like once a month… I think the quality of her food suffers a lot because of this situation because we live so far from the grocery stores."

Jennifer shared a photo of a packed freezer and the small local store to illustrate the challenge of accessing fresh food. “That’s shopping — the finest shopping we have around here… It's about the only outing that she gets to do besides church."

Recommendations and Potential Solutions for the Shortages

To tackle this workforce shortage, “The priority needs to be raising wages and offering benefits to these workers,” Chapman said. Potential solutions offered by Chapman, Sage, and colleagues include:

- Raise wages and offer job benefits. Personal care assistance has to be a recognized and appropriately compensated job. Benefits should include health care, but also childcare subsidies or education benefits.

- Incentivize workers in potential shortage areas and compensate them for travel time and costs. PCAs need to be compensated for the “windshield time” required to get to clients’ homes. One of the major challenges these workers face is transportation costs. If a PCA’s car breaks down, there is generally no public transportation to get them to work so it is essential that they are supported in their ability to get to and from where they need to go.

- Enhance workforce data collection efforts. Geographic data on the availability of personal care aides is limited, especially in less populated areas. Better data collection at the state and national levels can help increase recruitment and retention in underserved areas.

- Bring rural personal care aides and adults with self-care disability into the conversation. Policy decisions should be informed by the people most deeply impacted — the workers and the people they serve.

Research from Healthforce Center at UCSF and the UCSF Health Workforce Research Center on Long-Term Care offers essential knowledge on the long-term care and in-home workforces. The Research and Training Center on Disability in Rural Communities at the University of Montana are leaders in researching key issues related to rural living for people with disabilities. Visit their websites to learn more about this important workforce and the populations they serve.