By Nabiha Siddiqui based on work by Sunita Mutha, Janet Coffman, Susan Chapman, and Rebecca Hargreaves, Healthforce Center at UCSF

Photo: From the left: Maryam Alehashem, postdoctoral scholar, Berliza Soriano, doctoral student, and principal investigator Allison Williams, PhD, assistant professor at the UCSF School of Medicine, in the all-women, racially and culturally diverse Williams Lab, in Genentech Hall, at the UCSF Mission Bay campus.

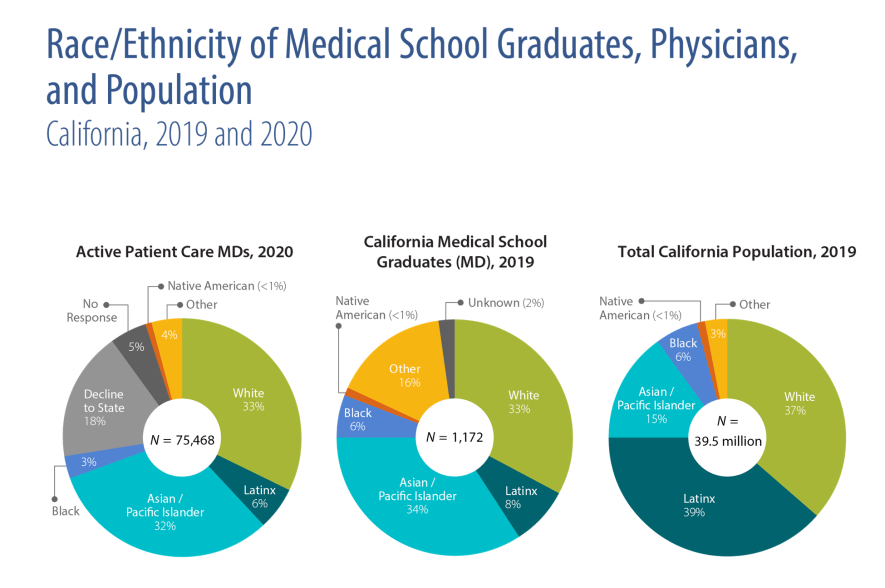

California is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse states in the nation, yet its health workforce does not reflect this diversity, especially for Latino, Black, or American Indian health professionals. (See figure below.) This lack of diversity is even more stark among the 45% of the workforce that comprises clinical roles that require advanced degrees such as nurses, therapists, doctors, and other clinicians. In 2020, Latinos represented 39% of California’s population, but only 6% of the state’s physicians and 8% of the state’s medical school graduates.

At Healthforce Center, we have long known that a diverse health care workforce supports positive patient experiences and equity in health outcomes. Individuals are more likely to seek care and adhere to treatment plans when they have racially and ethnically concordant clinicians. Patients receiving care from concordant clinicians report better communication and more trust and feeling more respected and understood.

Source: California Physicians Almanac, 2021: A Portrait of Practice, Janet Coffman, Emmie Calimlim, and Margaret Fix, California Health Care Foundation, March 2021.

After decades of research on this issue, we at Healthforce Center have a clear view of approaches that will increase workforce diversity, as well as the areas where additional research is needed. Many promising solutions also need to be tested to ensure that widespread implementation leads to better care for communities.

Factors that limit workforce diversity include a lack of exposure to role models and mentors, disparities in academic preparation, difficulty obtaining access to required courses, inadequate and biased career advising, and the financial cost of education. Such factors manifest at every stage of education from K-12 through collegiate, graduate, and post-graduate training. These factors extend into the workforce and affect the ability to climb career ladders and ultimately result in unequal advancement opportunities and wage disparities. (See here, here, and here.)

Structural racism is a pervasive factor in many of these obstacles. For example, many people in racial/ethnic groups that are underrepresented in health professions that require advanced degrees are educated in K-12 schools that lack the resources to adequately prepare students for college. Therefore, the solutions to increasing workforce diversity must be embedded throughout our educational and health care systems. Promising approaches that need demonstration pilots to support adoption:

- Shortened training pathways for select job categories that prioritize diverse cohorts of learners

- Access to learning and networking opportunities to ensure pipelines and mentoring for underrepresented individuals in training

- Leveraging innovations, such as distance learning, to broaden access to programs for rural and Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) participants

- Expanded social supports (such as childcare assistance) to enable entry-level and middle-skill workers, particularly BIPOC, to participate in the workforce and in career ladders

- Educating and supporting employers on effective strategies for recruiting and retaining diverse health workers

Below are aspects of these solutions that would benefit from additional research and testing to support scaling and spread:

- Assess which types of support best suit groups. Support to help successfully complete trainings can come in multiple forms, such as financial aid, money for living expenses, mentors, and social supports like caregiving or childcare. Research is needed to determine which of these options are most valued by which types of learners and effective in ensuring their success.

- Support pilots of novel training programs. As a society, we generally assume that longer training programs result in a more skilled workforce, but evidence suggests that this is may not necessarily be true. More pilot programs are needed to test shorter-duration trainings, and other alternatives, and evaluations of programs to generate the evidence to support employers’ decision-making in hiring these workers.

- Identify strategies that engage employers to hire graduates of novel training programs. Armed with fresh evidence from the above pilots, we can share the data to motivate employers to hire graduates of novel programs while meeting organizational needs for a productive array of health care workers. Research to understand barriers to hiring graduates can inform the design of solutions. And creating partnership and commitments, such as employers agreeing to interview a percentage of program graduates, can increase hiring of graduates while meeting workforce needs for employers.

- Test virtual models to scale and spread education. Remote training has been an option for many years now, and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of it by educational and care delivery organizations. Different practices for remote training to overcome geographic, cost, and demographic barriers can be tested to increase access to education.

- Increase worker retention by addressing burnout. Investing in mental health support for health care workers is crucial to address the increase in depression, anxiety, and stress. Strengthening and expanding resources to address mental health challenges is especially needed for BIPOC workers. Organizations must also address secondary trauma often experienced by these same workers, such as burdens of increased workloads, risk of job loss, and the pressures of dependent care. Employers must also work to reduce stigma for workers seeking mental health services and supports by normalizing outreach and ensuring confidentiality.

Given the differences in types of workers and community needs, there is no simple, one-size-fits-all solution to boost workforce diversity. To meet the urgency of this moment, educators, employers, and policymakers need to know and use proven strategies while investing to discover new ways to grow a diverse workforce that reflects the community being served.

Healthforce Center’s experts are eager to pursue further research and develop solutions to fill society’s demands for a diverse workforce to ensure delivery of quality and equitable care, as well as to provide consulting and guidance on solution implementation. The time is now for bolstering the diversity of our caregivers across all sectors of health care.

Related Content

- "What I'm doing about Black doctors being pushed out of medicine," Vanessa Grubbs, MD, 10/24/2022.

- Four medical students voice their experiences in a video from the California Health Care Foundation.

- "California lacks Black doctors. Here’s how the state can add more," Wynton Sims, CalMatters, 11/02/2022.

- "It’s an epidemic the health care industry is still trying to cure — its own racism," Shwanika Narayan, SF Chronicle, 10/13/2022.

- "A doctor who’s trying to fix what’s broken," University of California Newsletter, 2/15/2022.